Kids everywhere love to play. And they know that a ball is a perfect thing to play with. Now scientists at London’s Queen Mary University report that bumblebees seem to know the same thing, making bumblebees the first insects known to play.

When scientists talk about “play”, they’re describing an animal doing something that doesn’t really seem to help it. They’re not doing the action to get food or shelter or another similar “reward”. Play usually happens when a creature is relaxed. The behavior is often repeated.

(Source: Screenshot, Galpayage et al. [CC BY 4.0], Science Direct.)

Lots of animals play. But the behavior is best known in mammals and birds. For many animals, playing is often seen as a kind of training for things they’ll have to deal with in later life. But before this, there were no reports of insects playing.

Dr. Lars Chittka of Queen Mary University began to wonder if bumblebees played during an earlier experiment. In that experiment, Dr. Chittka trained bumblebees to roll balls into a goal for food. He noticed that some bees were rolling balls even when they weren’t rewarded. He wondered if they were playing.

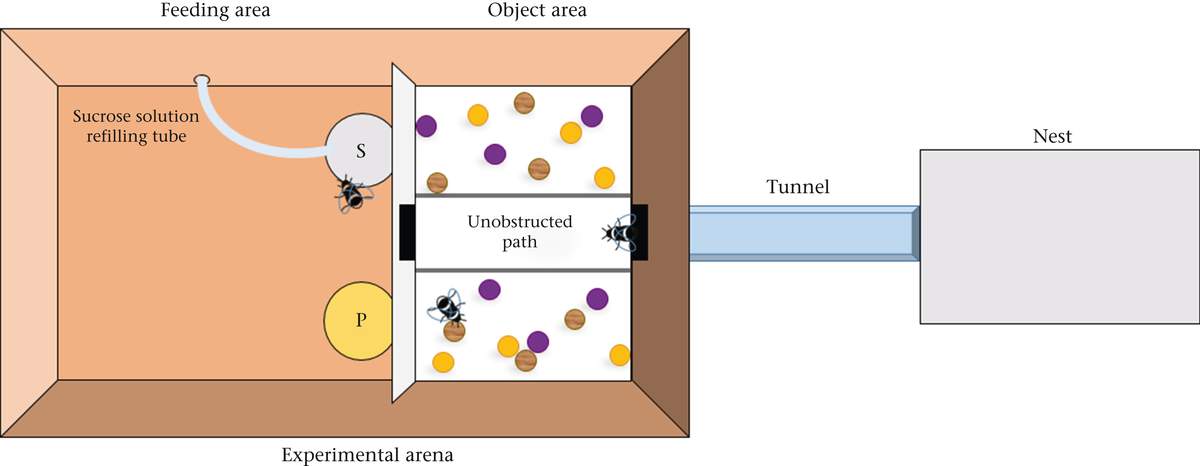

To test the idea, scientists at Dr. Chittka’s lab, led by Samadi Galpayage, set up a new experiment. First, they tagged 45 young bumblebees, both male and female, between one and 23 days old. The tags let them identify the bees and follow their behavior.

(Source: Galpayage et al. [CC BY 4.0], Science Direct.)

The scientists set up a clear pathway from the bumblebees’ nest to a feeding area. On either side of the open pathway, the researchers placed small colored wooden balls. On one side of the path, the balls were attached and couldn’t move. On the other side, the balls could roll around.

For three hours a day, over 18 days, the scientists opened the pathway between the nest and the feeding area. The bumblebees never had to leave the pathway to find food, but they left anyway. They weren’t so interested in the side where the balls didn’t move, but they made lots of visits to the side with the rolling balls.

(Source: Galpayage et al. [CC BY 4.0], Science Direct.)

Grabbing the balls with their legs, the bees would flap their wings to pull on the balls, causing them to roll. The 45 tagged bumblebees did this 910 times during the experiment. Though some only did it once, others did it a lot.

One bee was recorded rolling balls 44 times in a single day. One was seen rolling balls 117 times over the whole experiment. The scientists say the younger bumblebees spent more time rolling balls. Males seemed more likely to play than females.

(Source: Galpayage et al. [CC BY 4.0], Science Direct.)

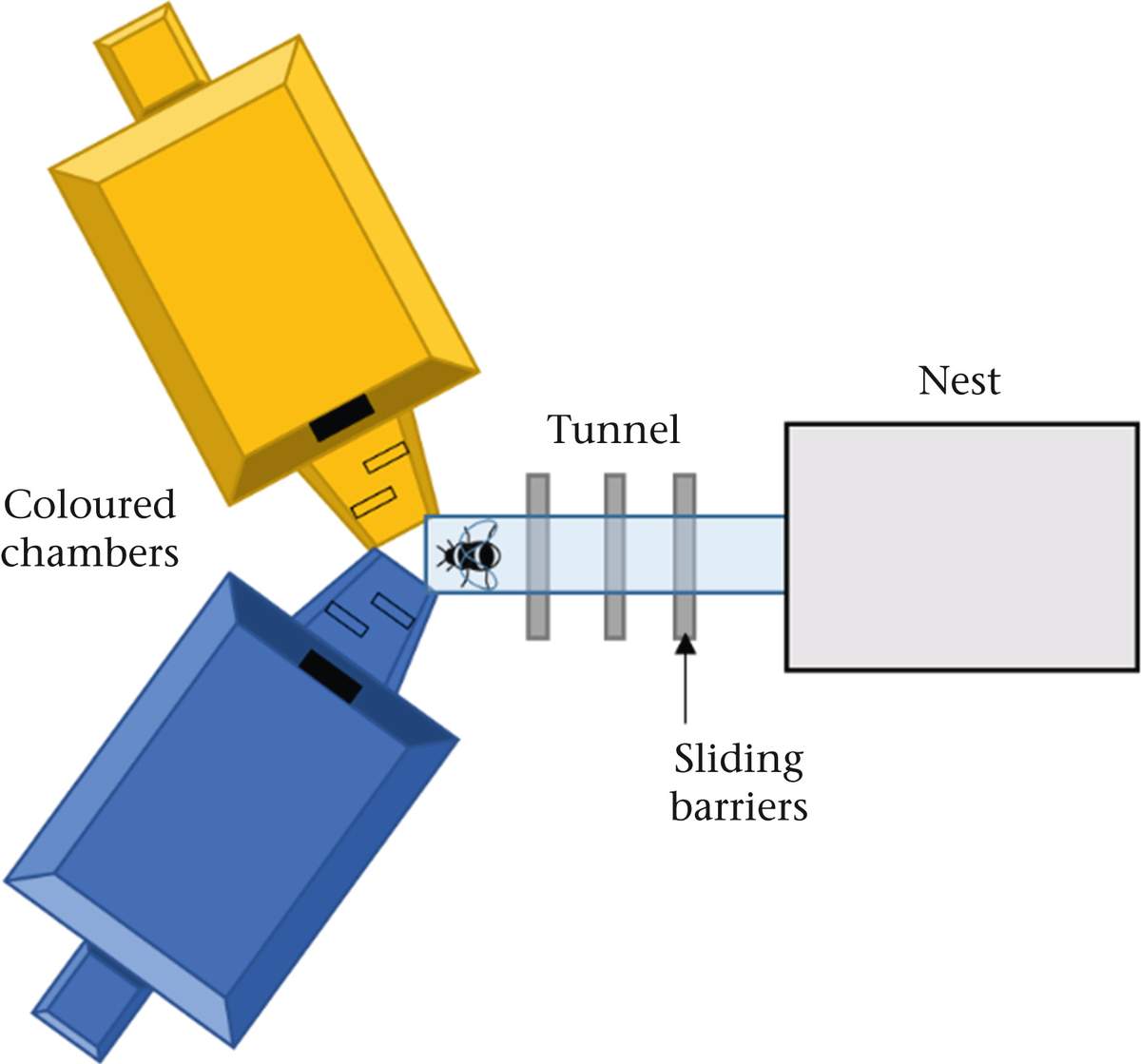

Next, the researchers ran a different experiment. They trained the bees to expect ball-rolling in a container of a certain color. Later, the bumblebees were given a choice between two empty containers of different colors. They were far more likely to choose the color where they had learned to expect ball-rolling.

The scientists say it’s not clear why the bees roll the balls or whether they enjoy it. But the experiment raises important questions about how the insects’ minds work and whether they have feelings.