Bariloche, Argentina —(Map)

Scientists have recently discovered that Andean condors – some of the world’s largest birds – barely flap their wings at all while flying. Instead, they use rising air currents to remain in the air for hours.

The Andean condor is the world’s largest soaring bird. Soaring means flying high with very little flapping. Andean condors are quite large. They can weigh up to 33 pounds (15 kilograms). Their wings, when spread out, measure up to 10 feet (3 meters).

(Source: WikimediaCommons.org.)

The birds are found in the Andes mountains along the Pacific coast of South America. The birds’ main food source are the bodies of large animals which have died. Soaring high in the sky allows the condors to easily spot possible meals on the ground.

Scientists from Swansea University in Wales and the National University of Comahue in Argentina worked together to study the flight patterns of these huge birds. They wanted to learn more about how much effort the birds use when flying.

(Source: Wer-Al Zwowe [CC BY-SA], via Wikimedia Commons.)

To study the birds while they were in the sky, the researchers attached special devices which could record every turn the condors made in the air, as well as every beat of their wings.

The scientists learned that most of the condors’ flapping – over 75% – came when the birds were taking off.

(Source: Wer-Al Zwowe [CC BY-SA], via Wikimedia Commons.)

Once in the sky, the birds flew for very long periods of time without flapping at all. In fact, they only flapped their wings for 1% of the time they were in the air. One bird flew for over five hours without flapping, covering nearly 107 miles (172 kilometers).

Soaring without flapping is important because birds burn energy every time they flap their wings. Think of the difference in the energy you use biking uphill compared with coasting downhill.

(Source: Hugo Pédel / France [CC BY-SA], via Wikimedia Commons.)

For birds as big as the condors, a lot of flapping would mean they would need a lot of food. Scientists knew that the condors soared much of the time, but they had no idea exactly how much.

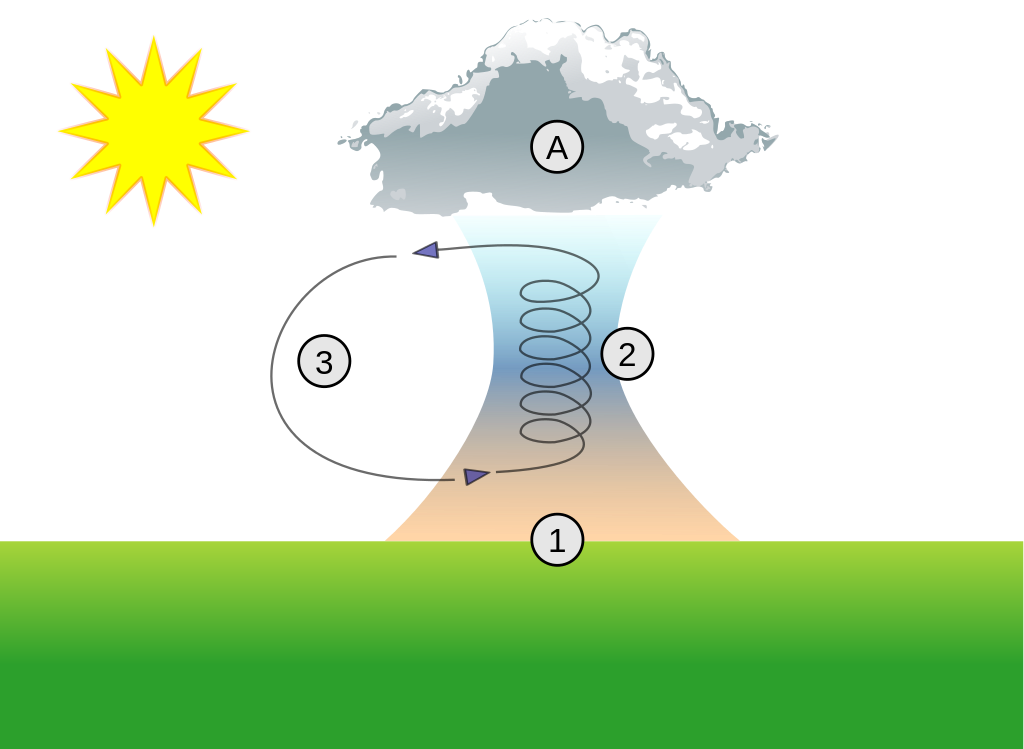

The birds’ soaring isn’t magic. They use the fact that hot air rises to keep themselves up. As hot air rises, it often creates “thermals” – currents of warm air moving upward. The condors hitch a ride on these thermals. The tricky part is finding thermals, and moving between them.

(Source: Dake [CC BY], via Wikimedia Commons.)

When the birds are forced to land and take off again often, it costs them a lot of energy. The researchers learned that to avoid having to land, the condors did most of their non-takeoff flapping when they were closer to the ground and looking for a new thermal.

The scientists reported that even though all of the condors they studied were young, they already knew how to take advantage of the air currents.

(Source: Ron Knight [CC BY], via Wikimedia Commons.)

The devices were designed to drop off of the birds automatically after about a week. Getting them back again was a challenge. Sergio Lambertucci, one of the researchers, said, “Sometimes the devices dropped off into nests on huge cliffs in the middle of the Andes mountains, and we needed three days just to get there.”

😕

This map has not been loaded because of your cookie choices. To view the content, you can accept 'Non-necessary' cookies.