Every year, as many as 50,000 elephants in Africa are killed illegally for their ivory tusks. Now scientists have improved DNA methods that allow them to match up tusks, and help track down criminal gangs that are selling the ivory.

Even though it’s against the law, African elephants have long been hunted by poachers for their ivory tusks. Other people, called “traffickers”, buy the tusks and smuggle (sneak) them out of the country on a ship. The traffickers re-sell the tusks for even more money, usually in Asia. Elephant tusks can sell for about $450 a pound ($1000 a kilogram).

(Source: WildAid )

Why Do People Want Elephant Tusks?

In some parts of Asia – especially China and Vietnam – many people think elephant tusks have special powers. They pay a lot of money for them. Sometimes the tusks are made into cups or art or jewelry. Sometimes they are ground into powder, which people eat because they think it is like medicine.

In the past, it has been hard to catch the criminals. Usually by the time the dead animals were found, the poachers were far away. And when traffickers were caught with tusks or horns, it was impossible to say where the tusks came from. Traffickers usually hide the tusks in tricky ways inside shipments of other products. That means that only about 10% of ivory from poached elephants is ever found.

Several years ago, scientists led by Dr. Samuel Wasser at the University of Washington figured out a new way to tackle the problem. Using elephant poop, they built a list of the DNA of almost all of the elephants in Africa.

(Source: Karl Ammann )

Now when tusks are found on a ship in another country, DNA tests can show where they came from. This information can lead to quick action in the country where the animals were killed. It can also help police discover patterns in the ways the poachers and traffickers work.

In 2018, Dr. Wasser and his team used DNA to match two tusks found in different shipments and show that they came from the same elephant. That meant that the shipments were connected. The discovery provided information about the way the traffickers worked, and revealed the ports often used by smugglers.

(Source: Center for Environmental Forensic Science/Univ. of Washington)

But matching tusks from a single elephant didn’t happen very often. So Dr. Wasser came up with a way of increasing the chance of matching tusks. He began looking at family DNA. There are enough similarities between parents and children and sisters and brothers to allow them to be matched through DNA.

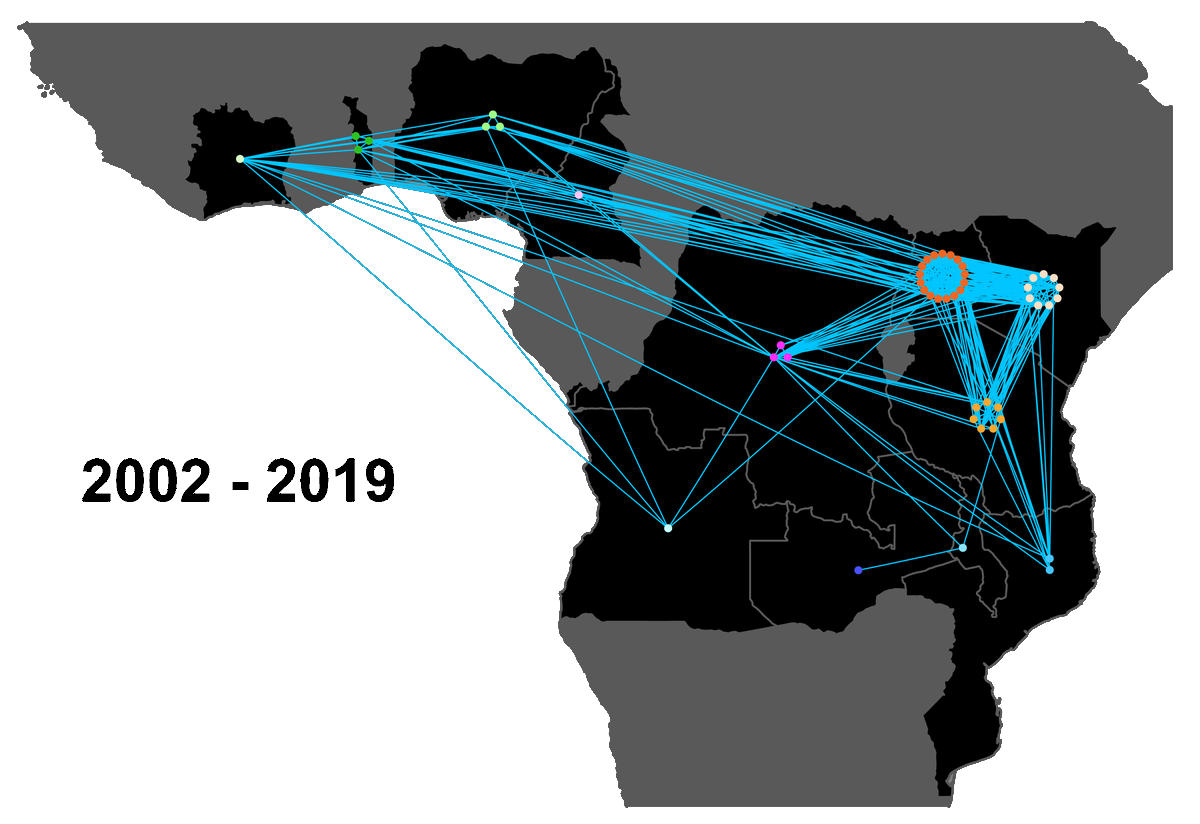

By checking DNA from animal families, the scientists were able to match far more tusks. The researchers took DNA samples from 4,320 tusks found in 49 different shipments between 2002 and 2019.

(Source: Kate Brooks )

The scientists found about 600 matches among the tusks. The matches told the researchers a lot about what was happening to the elephants.

They learned that there were only a few groups of criminals that kept going back to the same areas to get more tusks. The research also allowed the team to track how the ports used by the criminals changed over time.

(Source: Wasser et al. 2022, Nature Human Behaviour (adapted).)

As a result of the research, two animal smugglers were arrested in November. They could go to jail for over 20 years.

Dr. Wasser is hopeful that this method of using family DNA to track poached wildlife will soon help protect other kinds of animals and break up more criminal groups.