Scientists have come up with a new way of identifying animals in an area – by testing DNA sucked out of the air. The researchers believe their new method could help scientists keep track of animals that are hard to spot, including endangered animals.

Two teams of scientists – one in Denmark and one in the United Kingdom (UK) – came up with the same question at about the same time: Could they identify the animals in an area from DNA that was simply floating in the air?

(Source: Elizabeth Clare [CC BY-SA].)

DNA and eDNA

Every living thing, or “organism”, has DNA that can be used to identify it. All organisms leave bits of DNA behind them wherever they go – for example, from skin, hair, scales, feathers, or poop.

DNA left behind like this is called “environmental” DNA, or eDNA. Scientists can use this eDNA to tell what kinds of plants and animals are in a certain place.

Testing for eDNA isn’t a new idea, but most of the time, scientists look for eDNA in water. DNA in the air is usually so small that it would take a microscope to see it. The scientists didn’t have high hopes for their experiment. “We did not think that vacuuming animal DNA from air would work,” said Dr. Kristine Bohmann, one of the scientists on the Copenhagen team.

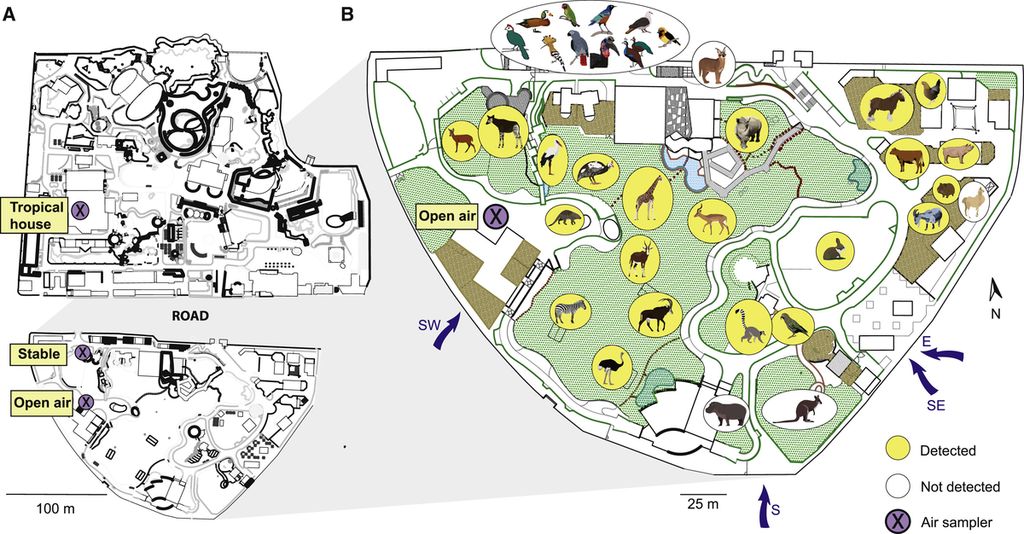

Neither team knew that the other group was working on a similar experiment. One collected samples from different locations at Denmark’s Copenhagen Zoo, and the other at Hamerton Zoo Park in the UK. The scientists used slightly different methods to collect their samples. But basically, both teams used vacuums and fans to collect extremely tiny bits of DNA onto very high quality filters.

(Source: Christian Bendix [CC BY-SA].)

In the laboratory, they got the DNA from the filters and made copies of it to study. By comparing their samples with examples of DNA from different animals, the scientists were able to identify many different animals at the zoos.

The researchers in Denmark identified 49 different kinds of animals, including mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish – even guppies in a pond. The team in the UK identified 25 different kinds of animals, including tigers, lemurs and dingoes. They even identified DNA from animals that were inside sealed buildings.

(Source: Lynngaard et al. 2022, [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0], Current Biology.)

The scientists chose to test in zoos because they had rare animals not naturally found in the area. As Dr. Elizabeth Clare, who led the UK team said, “There’s no other way I would detect DNA from a tiger, except for the zoo’s tiger.” But the researchers also detected some non-zoo animals, including humans, and a hedgehog that’s endangered in the UK.

Each team only discovered about the other experiment after they had written a paper about their own results. Instead of competing, the two decided to combine their results and publish a paper together.

(Source: Christian Bendix [CC BY-SA].)

Both teams are excited about the ways this new method could be used in the wild. Scientists have been looking for better ways to track endangered animals without interfering with them. If researchers know where animals live, they can do a better job of protecting them. “The next step is to figure out how to take this method into nature,” says Dr. Bohmann.